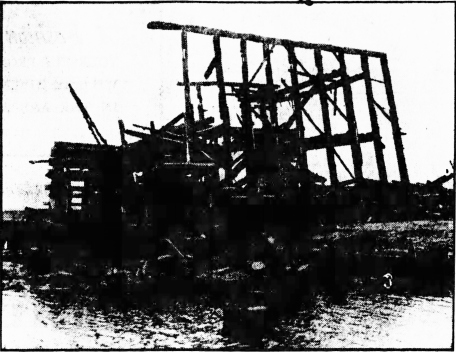

The celebration of July Fourth was truly a community event in the Brooklyn of a century ago. On 5 July 1912 the Brooklyn Daily Eagle published a full-page account of the day’s fesitivities, devoting a few paragraphs to each neighborhood’s offerings. In Gravesend, school children waving flags paraded through the streets to the grounds of the closed but not-yet-demolished Brooklyn Jockey Club (a.k.a. Gravesend Racetrack), where the winners of various foot races received medals like the one seen here for the 100-yard dash. Thanks to the Eagle, we know it was awarded to William Faith (see the transcription below). According to the 1910 census, he was William H. Faith, a son of Joseph and Anna Faith, who lived at 234 Van Sicklen Street. William was about 15 in 1912. (The Faith family moved to Queens by 1920.)

Obverse of medal presented to William Faith, winner of the 100-yard dash, Gravesend, 4th July Celebration 1912 (Collection of Joseph Ditta)

Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Friday 5 July 1912, p. 5, col. 4:

2,000 Children Enjoyed the Day at Gravesend.

The programme for the observation of a Safe and Sane Fourth of July in the Gravesend section of Brooklyn, held under the auspices of the Gravesend Board of Trade, was one full of pleasure for the youngsters in that locality. The festivities, which commenced at 9 A.M. were continued up to a late hour last night.

The children of the Marlborough [sic] and the Edinboro sections met at Gravesend avenue and Avenue P, whence they proceeded to Public School No. 95, in Van Sicklen street and Neck road, where the parade started.

At 9:45 A.M. the line formed in the road in front of the school and each child was provided with a flag. Then, escorted by a delegation from the Gravesend Board of Trade, and headed by the Thirteenth Regiment Band, which was followed by a boy and girl dressed as George and Martha Washington with an old negro attendant, the line moved forward along Van Sicklen street to South Village road then to East Village road, to North Village road and back to Van Sicklen street, thence to Kings Highway, where is [sic] was joined by the children of the High Lawn section. Then the parade, with over 2,000 children in line, proceeded to Gravesend [now McDonald] avenue, to Avenue T entrance of the Brooklyn Jockey Club’s race track, marching to the old betting ring, where, after the flag raising, during which those present sang patriotic songs, Senator James F. Duhamel made a short address to the children.

At 11 o’clock all the children were served with milk and cake. Following the refreshments came the athletic events. These took place on the track in front of the judges [sic] stand. The summares [sic?] were:

- 60-Yard dash for boys between the ages of 8 and 9 years—Won by W. Ellwood; second, W. Short; third, Bertran [sic] Van Buskirk.

- 60-Yard dash for seniors—Won by W. Ellwood; second, Charles Crofte [Crofts?].

- 100-Yard dash for seniors—Won by William Faith.

- Junior broad jump—Won by Peter Luchelli [sic] with a jump of 10 feet 10 inches; second, Austin Mazzarelli.

- Senior broad jump—Won by William Hand with a jump of 12 feet 2 inches, with Thomas Hand a close second.

- Sack race—Won by Jack Mermaugh; second, Thomas Hand, third Jack Hennessy.

- 220-Yard dash—Won by Wilfred Van Sicklen; second, Walter Pau; third, Fred Pack.

- Two-mile race—Won by J.C. Faith; second, Lou Ross; third, Harry Ellwood.

- Potato-race for girls—Won by Emma Fowler; second, May Maloney; third, May Dougherty.

At the conclusion of the games all those present were served with ice cream, cake and milk.

The feature of the afternoon was a ball game between the “All McCoys” and the “Board of Trade.” The players on each team were married men, and their plays were loudly applauded. The game was to be a regulation nine-inning game, but as a result of the heavy hitting the bat was soon split and the players were beginning to feel the presence of long forgotten muscles, causing the game to be called in the sixth inning, the decision being given to the “All McCoys” with a score of 9 to 7.

The line up of each team was a[s] follows: “All McCoys,” Hagle, catcher; Thompkins, pitcher; Van Sicklen, first base; Hart, second base; Down, shortstop; J. McCoy, third base; Martin, left field, and W. McCoy, right field. “Board of Trade,” Lorimer, first base; Bergen, second base; Bush, shortstop; Crofton, third base; Howard, catcher; Rucker, pitcher; Doremus, right field; Smith, left field, and McHune, center field.

The ball game completed the programme for the afternoon. At 8 P.M. there was a grand display of fireworks and a band concert at Second street, West street and Kings Highway.

After the fireworks the celebrants proceeded to the race track where dancing was continued until a late hour.

Theodore J. Smith was chairman of the Fourth of July Committee and D.C. Young of the athletic committee. The judges of the games were Jacob Stryker, Melville Ketcham and Clarence R. Van Buskirk; the starter man was L. Hardenberg, and D.C. Young was clerk of the course.

Sounds like a fun time was had by all!

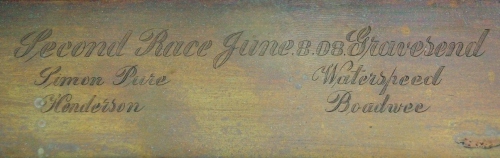

Reverse of medal presented to William Faith, winner of the 100-yard dash, Gravesend, 4th July Celebration 1912 (Collection of Joseph Ditta)

With her signature lyrical flair, Gertrude Ryder Bennett, described earlier but very similar July Fourth observances in Turning Back the Clock in Gravesend: Background of the Wyckoff-Bennett Homestead (Francestown, New Hampshire: Marshall Jones Company, 1982), 9-11:

Independence Day festivities around the Wyckoff-Bennett Homestead [at 1669 East 22nd Street] began in the morning, in a grove of ancient oaks in a triangle formed by the intersection of Kings Highway, East 19th Street and Avenue P. We gathered to hear patriotic speeches by Dominie Tibbles, Father Hickey and Rabbi Piper who spoke from a platform built for the occasion, while the listeners brought their own chairs or stood on the soft earth of the grove. Neighbor greeted neighbor. The tinkle of the hokey-pokey wagon had the effect, with the children, of the notes played by the Pied Piper of Hamelin. They broke away from their parents in the audience and, forsaking the eloquence of patriotism for a nickle’s worth of ice cream, they would cluster at the wagon, like humming birds after nectar. Then they popped caps on any hard surface they could find–minor explosions punctuating the day’s oratory.

Speeches over, families gathered in their own houses for the noonday meal, then reassembled in Edward Ridley’s meadow behind his elegant, Victorian mansion on King’s [sic] Highway [southwest corner of Coney Island Avenue].

Here, all afternoon, neighbors participated in the usual country games–potato races, three legged races, bag and wheelbarrow races. The baseball fans preferred to gather in the fields not far from our house and play ball. The married men played against the single men, with their women folk cheering from seats on planks placed on boxes. Their comments and good-natured banter filled the air like a musical accompaniment.

In the early evening, Mother, Father and I walked along Kings Highway to a block of street-dancing. We listened to the band awhile, then returned home for what I considered the cream topping of the day.

From the south end of our porch, we had an unobstructed view of the sky filled with bouquets of gorgeous flowers as Coney Island sent fireworks into the air. Today, with all the high buildings between our house and the ocean, it seems incredible. I watched in fascinated delight and always felt sorry when the final burst of splendor, accompanied by a large boom, lighted the sky. Then till midnight, the neighborhood boys set off their own firecrackers, while adults cringed with the noise and worried over possible catastrophies [sic]. It usually took a day or two to recover from this holiday.

Copyright © 2011 by Joseph Ditta (webmaster@gravesendgazette.com)