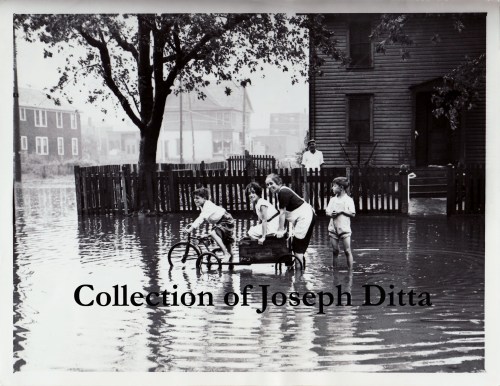

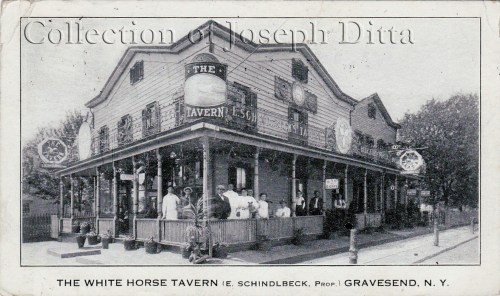

Sally Gil, “Edges of a South Brooklyn Sky,” 2018. Sea Beach line, Avenue U station, Manhattan-bound platform. Fire Engine Company 253 (center), New Utrecht Reformed Dutch Church (second from right).

Riders of the N train (a.k.a. the Sea Beach line) in southern Brooklyn have been tortured since 2015, when the MTA began work to revitalize the system’s nine crumbling, open-air platforms and station houses. Constructed between 1913 and 1915, the line remained largely untouched for a century, with maintenance limited to slathering on layers of beige paint in futile attempt to mask decades of exposure to vandals and the elements.

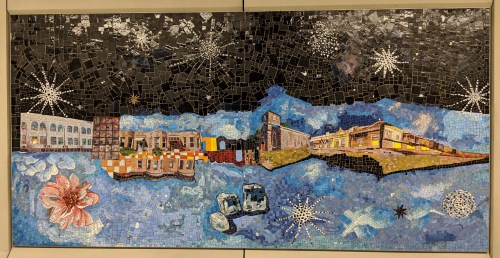

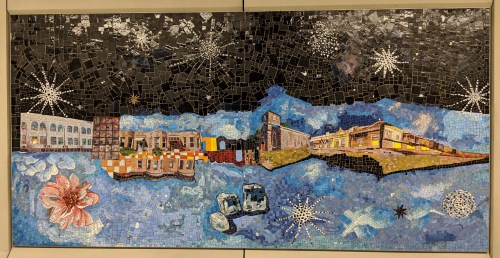

Sally Gil, “Edges of a South Brooklyn Sky,” 2018. Sea Beach line, Avenue U station, Manhattan-bound platform.

To “expedite” renovations, the line shut down in stages, first the Manhattan-bound platforms, then the Coney-Island bound side. After nearly four years of being forced to ride several stops in the wrong direction to catch a train running the opposite way, things are finally nearing completion. At Avenue U both platforms are open once again and both station houses are looking better than ever, although the one at the southern end is not quite finished as of this writing.

Sally Gil, “Edges of a South Brooklyn Sky,” 2018. Sea Beach line, Avenue U station, Manhattan-bound platform. Magen David Synagogue (upside down, at left), P.S. 95 (center).

I knew the MTA planned to include artwork as part of the Sea Beach improvements, as it had when it renovated the West End (D), Culver (F) and Brighton (B/Q) lines. Those stations are all elevated in this part of Brooklyn, so their artwork has taken the form of translucent panels that filter daylight through images and abstract patterns. Similar installations, but in mosaic tile, have started appearing along the N line, like the botanical-inspired splashes at 86th Street, and the big blocks of color at Bay Parkway, reminiscent of the Max Spivak mural uncovered at 5 Bryant Park in Manhattan.

Sally Gil, “Edges of a South Brooklyn Sky,” 2018. Sea Beach line, Avenue U station, Manhattan-bound platform.

Imagine my happy shock one recent morning when, after boarding a Manhattan-bound N train at 86th Street and snagging a seat, the doors opened at the next stop, Avenue U, and I looked up to see Lady Moody’s House on the wall! The doors closed, leaving me slack-jawed and straining to see what else was there as the train sped away.

Sally Gil, “Edges of a South Brooklyn Sky,” 2018. Sea Beach line, Avenue U station, Manhattan-bound platform. 62nd Precinct station house (center).

That night I couldn’t wait to get home to see if I hadn’t imagined it all. The station had no artwork the day before. But now, miraculously, it had fourteen mosaic tile panels, seven on the Manhattan-bound platform, and seven on the Coney Island side. Those on the Manhattan side show blue skies swirled with clouds and sparkly stars over a dark, asphalt-colored ground. On the Coney Island side, the sky is black and the ground a shimmery blue.

Sally Gil, “Edges of a South Brooklyn Sky,” 2018. Sea Beach line, Avenue U station, Manhattan-bound platform. Masjid Al-Iman Islamic Center (right).

Sitting along the horizon on each panel, sometimes at ground level, sometimes floating askew, and occasionally upside down, are familiar buildings from Gravesend and the greater neighborhood. It’s fitting that I spotted the Moody house first, but I instinctively knew so many more sites. They’re all so realistically done that it’s hard to believe they’re fashioned from small tiles and not painted on canvas.

Sally Gil, “Edges of a South Brooklyn Sky,” 2018. Sea Beach line, Avenue U station, Manhattan-bound platform. Van Sicklen (a.k.a. Lady Moody) House (right of center).

The places I recognize include

- Van Sicklen House (a.k.a. Lady Moody House), 27 Gravesend Neck Road, built early 18th century, (a designated landmark).

- Fire Engine Company 253, 2425-2427 86th Street, built 1895-1896 (a designated landmark).

- New Utrecht Reformed Dutch Church, 18th Avenue, built 1828 (a designated landmark).

- Rear of the house at 2066 West 7th Street between Avenues T and U, as visible from Coney Island-bound platform of the Avenue U Station.

- P.S. 95, 345 Van Sicklen Street.

Sally Gil, “Edges of a South Brooklyn Sky,” 2018. Sea Beach line, Avenue U station, Coney Island-bound platform. Antonio Meucci monument (center), Stryker House (right).

- Magen David Synagogue, 2017 67th Street, built 1920-1921 (a designated landmark); depicted upside down.

- 62nd Precinct Station House of the New York City Police Department, 1925 Bath Avenue.

- Masjid Al-Iman Islamic Center, 2015 64th Street, as visible from the Manhattan-bound platform of the 20th Avenue Station; depicted on two panels.

- Top of the house at 2076 West 7th Street between Avenues U and T.

- Top of the house at 30 Village Road North; depicted upside down.

- Monument to Antonio Meucci (1808-1889), inventor of the telephone, in Meucci Triangle, at the intersection of Avenue U, 86th Street, and West 12th Street.

Sally Gil, “Edges of a South Brooklyn Sky,” 2018. Sea Beach line, Avenue U station, Coney Island-bound platform. Hubbard House in silhouette (center).

- Top floor and tower of the Stryker house, 346 Van Sicklen Street, opposite P.S. 95.

- Hubbard House, 2138 McDonald Avenue, built circa 1830-1835 (a designated landmark); depicted in silhouette on three panels.

- Avenue U station house of the Sea Beach Line.

- Top floors of the houses at 71 and 75 Avenue U.

- New York State Education Department sign (1938) at the Gravesend Cemetery (the original of which reads: GRAVESEND | SETTLED IN 1643 BY ENGLISH | QUAKERS [sic] UNDER LADY DEBORAH | MOODY ON LAND GRANTED TO | THEM BY THE DUTCH | GOVERNOR OF NEW AMSTERDAM).

Sally Gil, “Edges of a South Brooklyn Sky,” 2018. Sea Beach line, Avenue U station, Coney Island-bound platform. Avenue U station house (left of center).

Architectural fragments–awnings, grill-work doors, and rowhouse cornices–are scattered among the panels, as are cups of coffee, a rainbow cookie, and loaves of bread. Tulips and other blooms breathe life into it all.

Sally Gil, “Edges of a South Brooklyn Sky,” 2018. Sea Beach line, Avenue U station, Coney Island-bound platform. Houses at 71-75 Avenue U (right).

If you have not been to the Avenue U station for a while, go examine these whimsical mosaics for yourself. Go early and plan to miss a morning train. Or linger when you get home at night. I promise it’s worth it. See if you can pick out the images I’ve listed. And tell me if you spot others I’ve missed.

Sally Gil, “Edges of a South Brooklyn Sky,” 2018. Sea Beach line, Avenue U station, Coney Island-bound platform. Masjid Al-Iman Islamic Center (left), New Utrecht Reformed Dutch Church (center).

The artist, Sally Gil, who calls her work “Edges of a South Brooklyn Sky,” was commissioned by MTA Arts & Design to create this permanent series using “found” places from the neighborhood to represent the diversity of its residents, present and past. She placed them along the horizon because that is where “the business of living happens.” As she explained by email, the objects in the mosaics “reference meaningful, mundane, iconic things and places in the neighborhood, all there for people to slowly (or quickly) realize they know.”

Sally Gil, “Edges of a South Brooklyn Sky,” 2018. Sea Beach line, Avenue U station, Coney Island-bound platform. Hubbard House in silhouette (left of tulips).

Gil’s original, small-scale, mixed media pieces were enlarged and fabricated in glass by Mosaicos Venezianos de Mexico. The artist hopes her work will remind us how “every day we are making our place in the world, and the subway is the conduit that transports us. We live on a physical plane while dwelling in our thoughts and imaginations–the world of our own stories.” We all have the same goal, Gil continues, “To live peacefully, with what we need and want.”

Sally Gil, “Edges of a South Brooklyn Sky,” 2018. Sea Beach line, Avenue U station, Coney Island-bound platform. Hubbard House in silhouette (left), Gravesend Cemetery sign (left of center).

Copyright © 2018 by Joseph Ditta (webmaster@gravesendgazette.com)